Rivers in Deep Time

Learning to live with rivers through a deep time perspective in a ‘dam’ned world.

by Mirza Zulfiqur RahmanWe often talk about the future like we’re running towards it. But more often than not, it feels like we’re running past something. As if we are always living at the edges and margins of time.

And when we talk about rivers, we often talk about floods, dams, and development.

But what if we spoke about time?

Not time as we know it - months, deadlines, elections.

But time as the Earth knows it - geological time.

The time it takes a river to cut through stone.

The time it takes for a mountain to rise.

The kind of time that can’t be reasoned with.

This is called deep time.

A way of seeing rivers not just as water bodies, but as living forces that have shaped our world for millions of years.

To care for a river, we have to understand its memory. And to understand its memory, we have to zoom out far enough, until we realise we are just a moment on the map.

The rivers, the mountains, they’ve seen entire civilizations come and go, while we have just arrived. Sometimes I wonder: is time part of the landscape? Or is time the landscape itself?

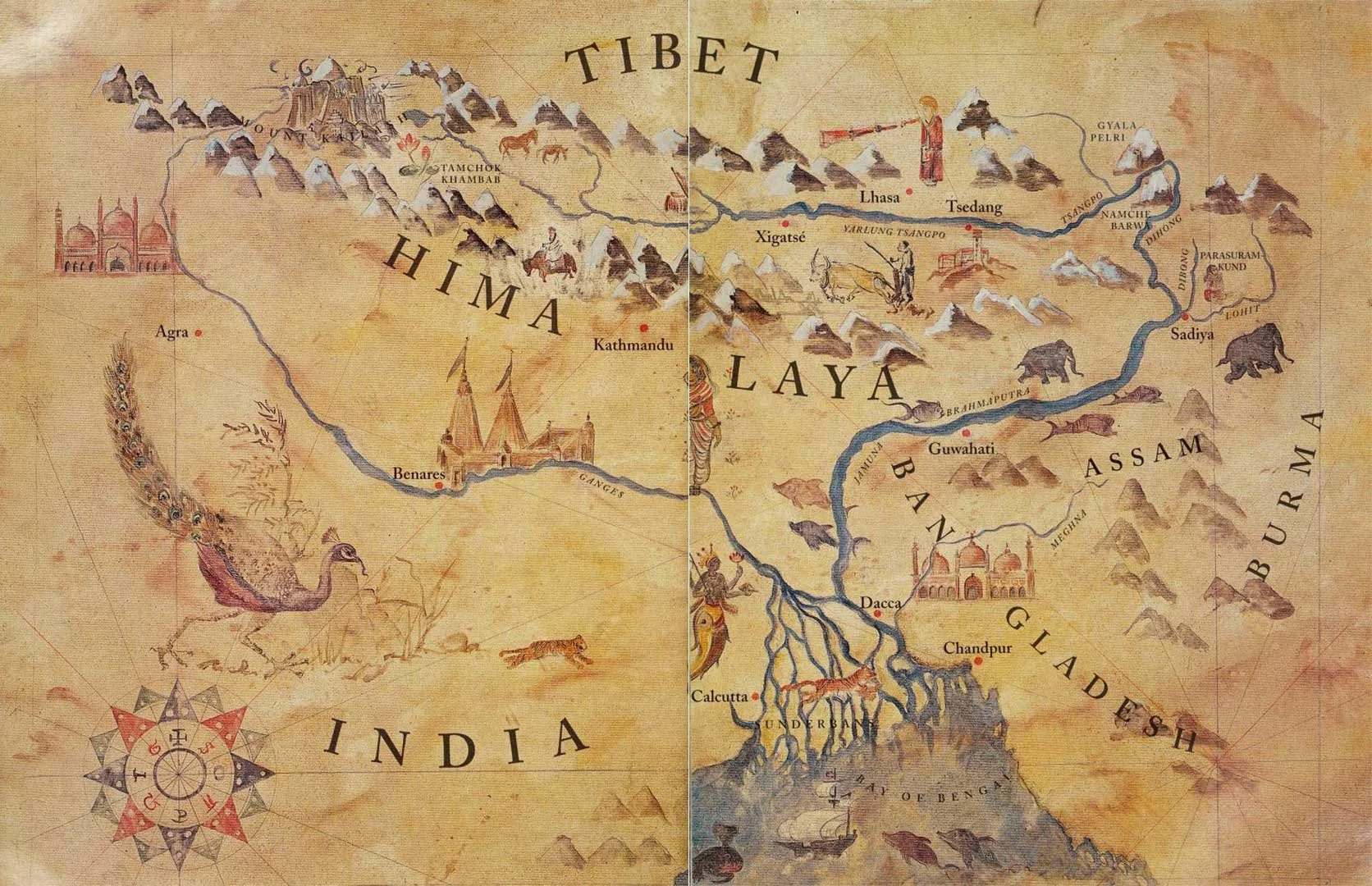

Image : A map from the book ‘Tales From The River, Brahmaputra: Tibet. India. Bangladesh’ by Tiziana and Gianni Baldizzone, archive.orgThe river is being dismantled.

And nobody is talking about it.

While climate change headlines fill our timelines, a more permanent shift is taking place. Right now, the Brahmaputra river is being cut apart.

In Tibet, China is building a series of massive dams at the headwaters, where the river is called the Yarlung Tsangpo. One of them, the Medog mega dam, will be one of the biggest in the world. It's being built at the Great Bend, a site sacred to local communities who believe it is the home of a goddess - Goddess Dorje Phagmo.

Further downstream, in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, India is preparing its own line-up of dams. The Siang, a major tributary of the Brahmaputra, is set to be divided into 36 separate projects.

This is no longer about control, regulation or development. This is dismemberment.

Once the river is carved into engineered parts, how do we put it back together again?

And if the river dies, if its flow, rhythm, and ecology are broken, what can ever replace it?

What is deep time, and why does it matter?

Let’s break it down.

We often think of time in terms of our own lives: school years, careers, deadlines, five-year plans.

But rivers do not think in five-year plans. They think in centuries, thousands of years, millennia.

Deep time is the time of riverbeds shifting, of monsoon patterns forming, of mountain ranges rising. It’s the time a river takes to shape a valley. To become home for somebody. Or to become a God for somebody living along it.

They don’t move according to our policies. They move with the wind, the monsoon, the mountains.

They’ve shaped everything around us, to see a river through deep time is to see it as a teacher. A master moody sculptor. A spirit living on through time.

And when we ignore this, when we try to force a river to follow our rules, we forget that we are just a moment in its long story, mere sediments in its vast unbounded flow.

The Brahmaputra

The Brahmaputra is no ordinary river. It’s moody, massive, and alive in ways we rarely acknowledge.

It roars in spring, sulks in winter, splits and reunites, shifts its path at will. It is both storm and stillness.

It shapes not only the land, but the worldview of everyone who lives beside it. It teaches us about what is fixed, and what is fluid. About how identity can shift. How nations draw borders, and rivers unshackle them with their flows.

It is a sculptor of valleys and lives. A witness to rituals, displacements, births, and floods. It is sacred to many, and home to more. It has inspired both politics and poetry.

And yet, in the name of development, we are trying to rewire something that has outlived kings and cartographers.

The people

We speak of displacement like it’s a single event. But along the Brahmaputra, it is a constant pressure. Communities lose land, rhythm, routine. They lose the memory of how they belong to a place.

The people of the river have spent centuries learning its moods, reading its shifts. Their knowledge isn’t theoretical, it’s seasonal and practical. But today, that knowledge is sidelined by blueprints and feasibility reports.

The Siang, also known as Ane Siang or Mother Siang, is planned to be divided into 36 fragments. Thirty-six. People are told they’ll be compensated. But how do you compensate someone for dismembering their Mother?

And when compensation arrives, if it arrives, it rarely understands the depth of that loss.

They’ve been adapting to the river’s moods for generations. They know its floods, its dry spells, its shifts. Their knowledge is lived, not learned from books. But this knowledge is being ignored in favour of concrete plans of nation-state bordered geopolitics.

The politics of control vs. the practice of care

Can a river that predates our borders be governed by our bureaucracies?

Can the fate of a transboundary river system be decided by national interest, when its spirit is older than the nations themselves?

The Brahmaputra is caught in a geopolitical race. China and India are both carving it up under the logic of “if they do it, so must we.”

But what’s lost in this race is the river’s right to exist as itself, not as a power source, not as a border threat, but as a being. What’s needed is not just treaties. It’s a shift in language. In imagination.

A river cannot be managed in fragments. It must be understood in flow. Through flood songs. Through migration patterns. Through rituals that mark its changes. And to do that, we must listen to those who have lived with the river. The river doesn’t care about borders. But it will respond to what we do. And if we continue to treat it like a resource instead of an ancestor, it may stop giving life, and start taking it.

A book to read if you care about rivers of deep time

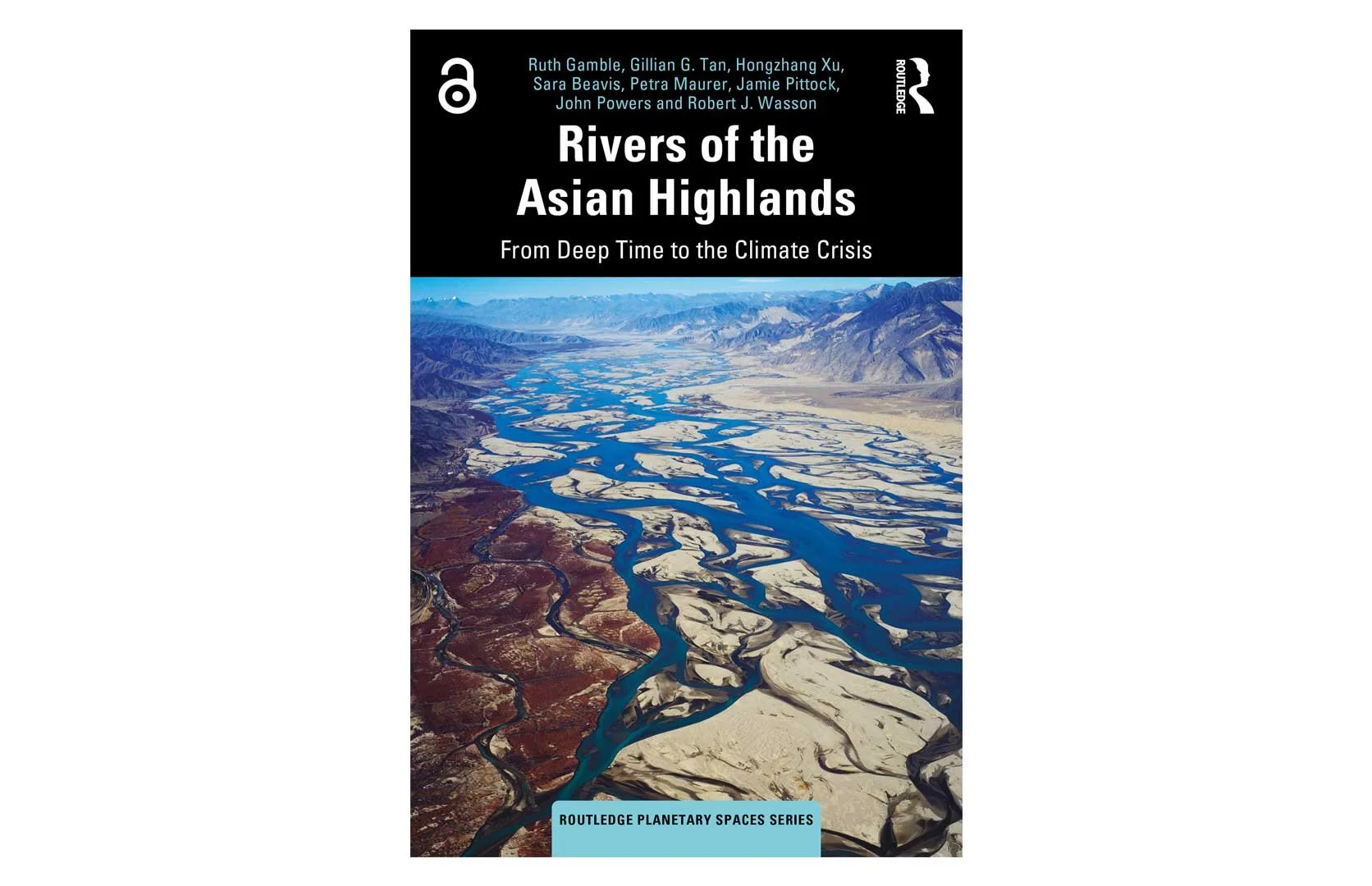

Rivers of the Asian Highlands: From Deep Time to the Climate Crisis is a vital book for our times.

Written by Ruth Gamble, Gillian G. Tan, Hongzhang Xu, Sara Beavis, Petra Maurer, Jamie Pittock, John Powers, and Robert J. Wasson, it explores the stories, crises, and meanings of rivers across the Asian Highlands.

It brings together voices from science, culture, history, and lived experience to show how rivers are so much more than just physical flows. It offers a braided view of rivers, just like the rivers themselves, which twist and turn, split and merge.

(Most rivers flow in one broad channel of water, but some rivers split into lots of small channels that continually split and join each other to give a braided appearance. These are called braided rivers. The animations below show long-term changes to parts of the Brahmaputra River islands from 1988–2018. Many islands which had human settlements in the 1990’s are now being eroded away. Source: NASA Landsat.)Most importantly, it connects the macro (climate crisis, international policy) with the micro (local knowledge, seasonal rhythms), a blend I believe is essential if we’re to have any hope of protecting rivers like the Brahmaputra.

It is a book I hope more people will read.

The book explores what it means to live with rivers through deep time. It shows us rivers as social, spiritual, and ecological systems. And it reminds us that saving a river is not just about stopping a dam. It’s about changing how we see the river in the first place.

I recommend this book not just as a scholar, but as someone who has spent years listening to this river, and learning to walk at its pace, live and flow along its moody meanders.

Resource list:

1. Read the book here - ’Rivers of the Asian Highlands: From Deep Time to the Climate Crisis’ By Ruth Gamble, Gillian G. Tan, Hongzhang Xu, Sara Beavis, Petra Maurer, Jamie Pittock, John Powers, Robert J. Wasson, is an open access book.

2. Visit NE India WaterTalks - an archival platform of water stories from Northeast India. It also acts as a workspace for the people working on water for the region. NEIWT visualises a water secure and sustainable region based on the principles of social equity, environmental sustainability, democratic and inclusive water governance.

3. Visit vikalpsangam.org - that has emerged out of a search for grounded alternatives to the current model of ‘development’ that is built on ecological destruction and rising inequalities.

4. Visit Heinrich Boell Foundation's South Asia Bioregionalism Working Group - a voluntary network of members reimagining an ecoregional and bioregional governance for South Asia. About the contributor

Mirza Zulfiqur Rahman holds a PhD in Development Sciences from the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Guwahati. He studied International Relations and Diplomacy at Jawaharlal Nehru University and earned his undergraduate degree in Political Science from Hindu College. His areas of interests include research on Northeast India, mainly on issues relating to transboundary water sharing and hydropower dams, roads and connectivity infrastructures, conflict and insurgency, peace building, development politics, migration and cross border exchanges. His research specialization is on border studies in Northeast India and transboundary water sharing and management issues between China, India and Bangladesh.